It is the end of an era for Germany – and not just because Angela Merkel is stepping down from the helm after 16 years. Germany has for years been Europe’s largest economy, the spearhead of the EU, a stable democratic nation and a pioneer of industrial sectors. But today, it faces challenges that can no longer be tackled by ‘Merkelism’ – consensual governance, rooted in continuity and geared towards maintaining the status quo.

From being left behind in the technology and industrial race to climate change challenges, internal and EU level fiscal reforms and balancing the superpower rivalries – Germany as a country and leader of the EU requires disruptive decision making. However, from what is emerging in the election run-up – Chancellor candidates imitating Merkel’s style, lackluster party manifestoes and a polarized electorate – German elections are likely to produce ‘weiter so’.

A recent economist article stated how far Europe has lost its competitive industrial advantage in the sectors of the future. In early 2000, 41 of the world’s top companies were in Europe, today the number is only 15. A third of the combined value of the world’s 100 biggest listed firms and a quarter of profits was in Europe, it’s fallen by almost half. COVID-19 has exposed the slow and restrictive working of the bureaucracy in Germany and the EU that led to delayed vaccinations, fewer tests and masks. Some politicians also admit that COVID-19 brought out the limits to digitisation and social equality in the German economy. Brexit and the faltering relevance of NATO have raised questions on the European defence and security future. A recent study by the Institute of Foreign affairs showed that many EU countries still consider Germany as the de-facto leader of the EU. However, many Germans, including politicians, are less inclined to shoulder this responsibility, especially in the geopolitical landscape.

Also Read | France’s withdrawal: Will Sahel rise up to the evolving security dynamics?

Amid these challenges, German elections are likely to produce much of the same – unclear electoral mandate, protracted coalition negotiations between 5-6 parties, a common agenda to preserve continuity and cohesion rather than propelling innovation and change.

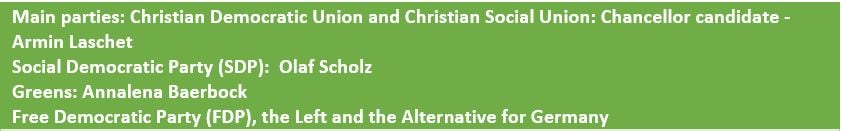

There are some breaks from the past. Merkel’s centre-right, Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and its Bavarian Union sister party CSU is trailing behind the centre-left Social Democratic Party (SDP) in these elections. The CDU/CSU has governed Germany for 52 out of 72 years. Today plagued by succession issues, an internal division between the CDU and CSU over the Chancellor nomination and appointment of uninspiring Armin Laschet has eroded its support base in many states. Olaf Scholz, leader of the SDP, currently leads the popularity contest but only with a 2-3 percent lead over the CDU. SDP itself has lost a sizeable vote share breaking the centre-right and centre-left hold over German politics. From winning 70-80 percent of the total vote share before 2017, neither party is expected to win more than 25- 28 percent vote share.

Possible coalition alliances:

| SDP + Greens + FDP | If SDP maintains its current lead, Olaf Scholz will be invited to form the government and this coalition will be possible. This group might be the most prudent in backing a looser budget policy and a common debt mechanism (fiscal policy) at the EU level. |

| CDU + Greens + FDP | If CDU leader Laschet manages an electoral turnaround, this alliance will be on the cards. A similar mechanism was tried in 2017 but failed when FDP pulled out. This time around the Greens might be less willing to sign up. The main conflict will be b/w reimposition of ‘debt brake’ that conservatives want with Greens demand of 10-year investment program |

| SPD + Greens + Left parties | Possible if FDP refuses to join SPD + Greens but is full of contradictions and not favourable for business and investment reforms. |

| Grand coalition (CDU and SPD) with Greens | The current Grand coalition b/w CDU and SPD has created discontent on both sides. Less preferred option |

| Grand coalition with FDP | Last resort as FDP has been a critic of previous Grand coalitions. |

But this decline of the centre has not translated into any clear alternatives. The Greens – led by Annalena Baerbock, had a rare chance to reshape the policy agenda with clear goals on the green economy supported by a ten-year investment program. However, their early lead (they are still polling at over 15 percent) was squandered due to scams related to Baerbock’s resume and her supplementary income from the party. The support has also held up for left parties and the pro-business Free Democratic Party. However, a fractured and polarised landscape has meant candidates espousing continuity and a watered-down version of their platforms since any government will result from a tripartite coalition.

Many possible alliance concoctions have already been tried at the national and state levels. German coalition building in 2017 took almost five months. This time around, the math might take longer or be more unstable in the absence of the master consensus builder Merkel. Decisions on the need to compromise on the ‘debt brake’ for more investments in a greener and digitised economy, loosening the bureaucracy to allow for entrepreneurship, military up-gradation and stands on China, Russia and the transatlantic alliance will lag around.

It will also lead to Germany being unable (as it manages its coalition compulsions) and unwilling to lead the EU. Combined with a similar situation after the French Presidential elections next year could spell trouble for EU reforms on three parameters – a) greater fiscal integration, b) upholding the rule of law in the face of authoritarian states and c) EU’s role in world affairs. In 2020 COVID-19 induced efforts led to the Next Generation EU Fund and the European Commission tapping the capital markets to raise Euro 750 billion to be deployed across the EU. However, most German candidates consider it a ‘one-off step’ with a return to some form of debt brake and a balanced budget by 2023. The next German leader is also likely to prioritise cohesion of the bloc over penalising habitual offenders of the rule of law and human rights – states like Hungary and Poland that are challenging the basis of the EU.

Also Read: Will the Quad add to the brinkmanship game in Asia?

The new leadership will also struggle to re-imagine Germany and the EU’s role in the changing geopolitics. Based on the manifestoes, debates and campaign speeches, there is little to indicate that the Chancellor candidates will move beyond Merkelism in this domain. For example, how to manage the contradictions of continuing economic relations with China while overlooking their tendencies of espionage, taking over of strategic assets and global aggression. To sanction Russia while allowing them to take advantage of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline. Particularly vital is the latest episode of Australia joining in the AUKUS (Australia, US and UK military partnership) and scrapping a French contract to purchase conventional submarines for a US nuclear-powered submarines agreement. The dynamics show that Europe is being marginalised in the main geopolitical theatre – the Indo-Pacific. Do the candidates, the polarised political landscape and the German population have the appetite for effecting the needed changes? – does not seem likely.

—The author Shraddha Bhandari is co-founder and CEO of Intelligentsia Risk Advisors, a strategy consulting firm. The views expressed are personal.

Resource: https://www.cnbctv18.com/views/london-eye-uk-goes-both-ways-on-the-economy-11030522.htm