Developments of the past few weeks have highlighted the push and pull that will be a part of the disruptive global transition from ‘dirty’ to clean energy. In June, two US oil giants ExxonMobile and Chevron, faced shareholder rebellion from the unlikely duo of climate activists and institutional investors for the failure to set out a low carbon growth strategy. A court in Hague ordered Shell to cut carbon emissions by 45 percent in the next 10 years.

Parallelly, China is facing its worst power crisis in a decade attributed to limits on coal usage, challenges of using renewable energy in extreme weather and surging post-pandemic demand. In the Middle East – state-run oil companies are planning to increase their market share as the companies in Europe and the US are forced to cut output. Amid all this, the technology war between the US and China is complicating the clean energy supply chain.

Given the environmental compulsions, while they move from fossil fuels to cleaner energy sources is writing on the wall, the transition will not be smooth or linear. Instead, it will be fraught with back and forth challenges – economic and supply chain disruptions, uncertain regulatory environment, and geopolitical hiccups. This article highlights the critical risks for stakeholders in the segment arising out of three trends:

1. Asian energy-intensive development model

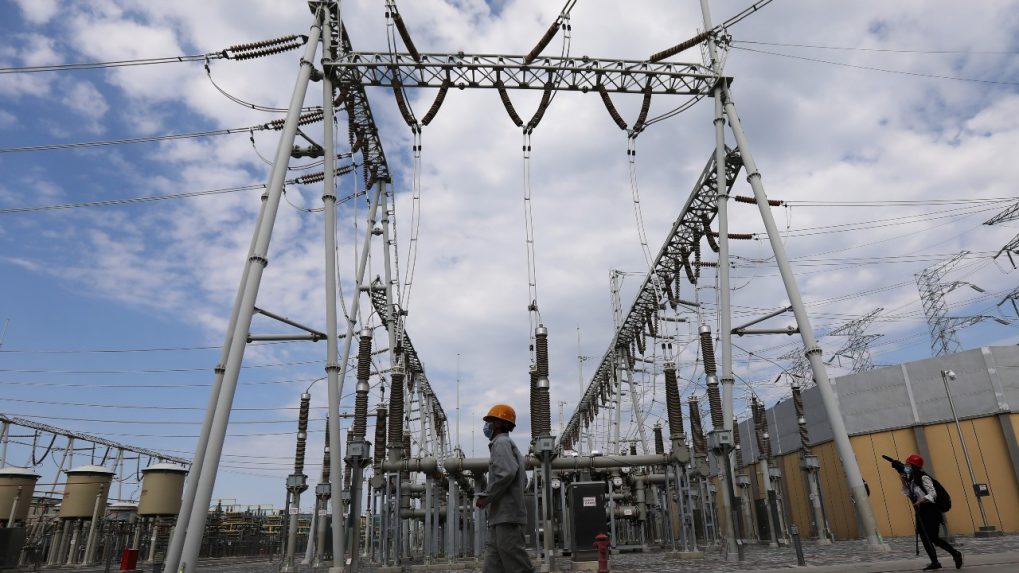

Since June, China is facing its worst power crisis in a decade. At least nine provinces, including Guangdong (10% of China’s annual economic output), manufacturing hubs of Zhejiang, Yunnan and Guangxi, have been rationing power for over a month. These restrictions have forced companies to shut down for a few days per week, leading to a (for now minimal) slowdown in factory activity growth in June. While China’s strong exports numbers have overshadowed reporting of these trends, it could be the beginning of bad news for the entire world – as these provinces also have the biggest share of China’s foreign trade. Along with Covid related production and shipping delays, they are now caught in a power crisis that can be systemic in nature.

Chinese policymakers are honing down on three likely, inter-related reasons, which will further complicate the move from ‘dirty’ to clean energy.

- Driven by primarily domestic compulsions, limits have been imposed on coal usage to produce electricity as a part of President Xi’s push for a carbon-neutral China by 2060. These compulsions include the need to control air pollution, phase out coal mines with lax safety procedures and fulfill China’s plans to control the future of green technology.

- The renewable sources have been unable to fill the gap, especially since the drought has hampered hydroelectric sources. The energy demand generated by China’s infrastructure-led heavy industry model is so voracious that despite strides in renewables and battery technology, it cannot be satiated without the use of coal (fossil fuels), at least in the short to mid-term.

- China’s post-pandemic recovery plan has focused on carbon and energy-intensive heavy industries and infrastructure. The coal-fired heavy industries made up 37 percent of economic activity last year and 60 percent of power generation in China is still coal-based. After this phase of power crunch – there are indications that provinces are planning to increase coal-fired generation and maybe open up plants that were shut in the run-up to 100 years of Communist Party of China’s formation on July 1.

The other Asian industrial powerhouses echo these themes – a recent International Energy Agency (IEA) report has highlighted that Asian countries have increased coal consumption as they seek to revive post-pandemic economic activity. This is not a reversal of policy towards a low carbon future but definitely a relaxation of stringent norms. Many Asian countries, while taking steps towards renewables and clean energy, have not formulated concrete strategies around phasing out of fossil fuels. The oscillation between meeting rising electrification needs and de-carbonization imperatives will create policy uncertainties.

2. Geo-politics of oil and gas

There is a global flip side to the climate activists’ wins against Western majors, highlighting the lack of global buy-in to switch to clean energy. The global oil and gas demand is far from peaking and these remain the most efficient, cost-effective fuels for a variety of developed and developing economies. While lawsuits, activist pressure and government emission targets are forcing companies in the US and Europe to cut their oil and gas output – Gazprom and Rosneft (Russia), Saudi ARAMCO and Abu Dhabi National Oil Company are under no similar compulsions. Today, western companies control about 15% of the energy market while OPEC and Russia possess 40 percent. This ratio has been relatively stable, with rising demand being met by new producers such as smaller private US shale firms. But as pressure mounts on western oil companies to cut output – state-run companies are likely to increase market share. Besides delaying the transition to clean energy, this will also increase the leverage of geopolitical ‘troublemakers,’ especially Russia.

3. Technology cold war

But the most significant risk to this transition will be the technological war between the US (and its allies) and China, with many countries forced to take sides. Today, China manufactures 1/3rd of global wind turbines, 70% solar panels, and 3/4ths lithium-ion battery cells. It has created dominance in critical minerals required for lithium-ion batteries (lithium and cobalt), solar panels, wind turbines, electric cars – through domestic production and securing mines in other countries. Put loosely – as China and US-led camps collide on technology issues – many countries, especially the US, are investing in domestic innovation and manufacturing and cooperating to counter the Chinese leverage. However, this will not happen overnight and in the short to mid-term – the options exercised will be trade restrictions, blacklisting of Chinese companies, and geopolitical pressure on developing countries to diversify supply chains from China. This politicization will fragment the global energy supply chain, making it expensive and inconvenient for developing countries like India to shift from fossil fuels to clean energy.

The move to clean energy is fait accompli and presents gargantuan opportunities as the world seeks to move from fossil fuels to efficient electrification, energy-storing technologies in sectors hard to electrify and strives to remove CO2 from the atmosphere. But with all major changes come disruptions, pushback, and vested interests. How one invests, at what stage and which technology, manages geopolitical risks, builds a diversified supply chain, and pre-empts potential back and forth – will determine who gains in this global clean energy race.

—Shraddha Bhandari is co-founder and CEO of Intelligentsia Risk Advisors, a strategy consulting firm. The views expressed in the article are her own